Challenging North Australian landscape management paradigms

Prompted by the personal observations of Chris Henggeler that span 40 years

I hear, I forget…

I see, I remember…

I do, I understand

… thank you for that quote, Jim!

What could pastoralism do for Australia, if consumers understood the challenges facing us in our back-yard?

Apart from remoteness, we are only limited by our imaginations. P. Tupman

Apart from remoteness, we are only limited by our imaginations. P. Tupman

How could the managers of pastoral enterprises justify the investment of time and effort in deteriorating catchment areas and neglected rangeland?

Informed purchase-choices of consumers need to support regenerative pastoralism in those areas where it is most needed. So, what must those who recognise the challenge do to facilitate such understanding?

The pastoral industry requires healthy functional animals.

The pastoral industry requires healthy functional animals.

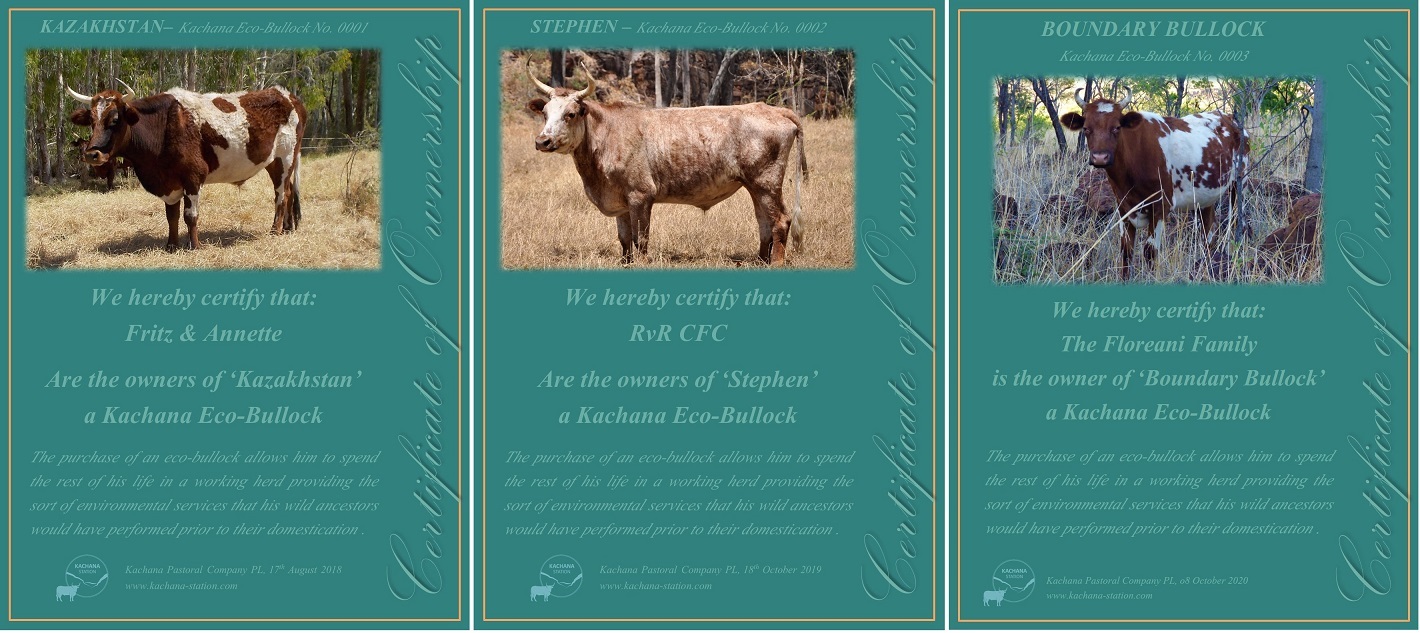

Industry uses animals primarily for breeding or slaughter, but Aaimals could also be put to work as landscape regeneration tools!

The purchase of an eco-bullock allows him to spend the rest of his life in a working herd providing the sort of environmental services that his wild ancestors would have performed prior to their domestication.

The purchase of an eco-bullock allows him to spend the rest of his life in a working herd providing the sort of environmental services that his wild ancestors would have performed prior to their domestication.

Much of uninhabited Northern Australia is at a stage where only functional herds could heal the land and rebuild and maintain water-security. Managing animal behaviour is the key. The relevant knowledge and according skill-sets have been tested and put to use in Australia for well over 20 years. To a back-drop of scepticism, public speculation and ongoing academic and political debate, science is fast catching up.

A working herd on Kachana; school holidays are a great time to recruit more hands!

A working herd on Kachana; school holidays are a great time to recruit more hands!

What is preventing the use of managed ‘free-range herds’ to provide the industry with export animals?

Corruption and greed might play a role, but I suspect that it has more to do with paradigms, faulty legislation, financial disincentives, peer-pressure, lacking education and skills…

What is preventing industry-players to boost the SDH (stock-days per hectare) in intensively managed areas whilst using managed ‘free-range herds’ to build water-security at catchment levels?

My bet is on paradigm-paralysis, faulty legislation, financial disincentives, peer-pressure, lacking education and skills…

Would a quadrupling of SDH justify a more elaborate use of permanent and temporary fencing?

Would a quadrupling of SDH justify a more elaborate use of permanent and temporary fencing?

It is heartening to see films like “Kiss the Ground” being made.

It is inspirational to hear about success stories like One Hundred Thousand Beating Hearts or Herd Impact.

It is also reassuring that when regenerative principles are applied, this also allows nature to work its magic in places like the Chihuahuan Desert Grasslands of Mexico.

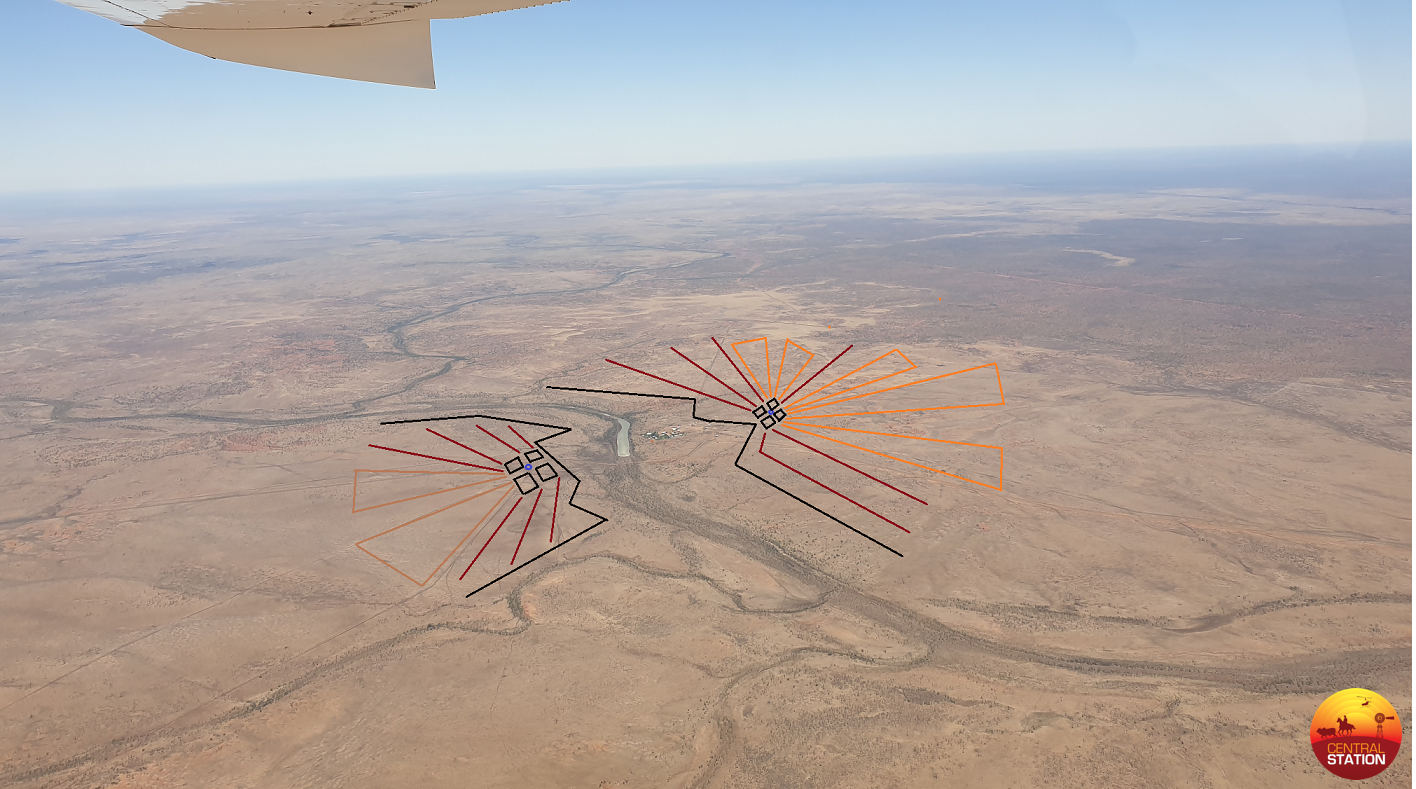

However, a recent 5254-kilometre low-level flight across northern Australia, reveals that politically-correct extraction of nutrients wins the day over sound custodianship of the nation’s natural resources. Hidden in plain view, it is now apparent that in Northern Australia the need for rehydrating landscapes surpasses the need to produce food.

Before they supply flow to river systems, functional savannah landscapes recharge groundwater and aquifers. Soils and groundcover need to act as a giant sponge to capture rain where it falls.

Before they supply flow to river systems, functional savannah landscapes recharge groundwater and aquifers. Soils and groundcover need to act as a giant sponge to capture rain where it falls.

This requires sufficient herbivores functioning in a manner that vegetation remains healthy. Healthy vegetation in turn feeds soil-organisms that build and maintain structure, enabling aeration and hydration.

Fortunately, Australian landscapes are now dotted with pastoral innovators blending new evolving knowledge and skill-sets with existing local knowledge to suit their particular contexts.

While this is good news for the food-system, this does not directly address the danger of increasing water-woes which manifest themselves in the form of alternating drought, flood and fire.

On parts of our properties where we have skin in the game, we are getting runs on the board. Visitors come and go, people say “Wow!” and films are being made. People forget and people remember, but are we reaching consumer understanding? (One must conclude: Not yet!)

Pastoral players could be playing significant roles in educating the consumer. However, they cannot do this on their own without neglecting what ought to be core-business: custodianship and the nurturing of natural resources.

Pastoral project partners could offer land, animals and skills. (Natural capital and social capital)

Projects would require facilitation, scientific scrutiny and evaluation. (More social capital)

Natural and social capital would need to be accounted for and reimbursed. (New injections of financial capital in a manner where ‘the tail does not wag the dog’!)

Should we drought-proof enterprises or drought-proof landscapes?

Should we drought-proof enterprises or drought-proof landscapes?

As is already happening at farmers’ markets in smaller towns, financial capital could flow via informed purchases. Only, we do not even require high-school math to appreciate that no amount of food-purchases by Australian consumers will suffice to impact the water-woes already confronting this nation. My feeling is that seed-funding (financial capital) would need to come from beyond the industry, i.e. from the greater economy which over previous centuries derived much of its momentum from the spoils of pastoral extraction.

High-profile demonstrations cum learning sites could deliver an international message:

Pastoralists can be land-doctors but they’d need to be valued as such.

Such sites could be the venue for hands-on training offered to environmentalists and aspiring land-doctors. Consumers could enjoy meaningful holidays whilst learning and understanding from the ground up, how their health, water and energy needs ought to be rooted in the landscape.

Do we design projects that can be taken to levels where they become self-funding?

Can we keep bureaucracy in check?

Could we attract departmental and political support?

Are there incentives in place for citizens and businesses to financially support or partner in such projects?

Ideally free ranging herds would include other managed herding herbivores!

Ideally free ranging herds would include other managed herding herbivores!

While I did outline the sad state of much of the country I recently flew over, maintaining a community endorsed ‘more of the same’ approach would allow for many more years of extractive practices. I therefore do not fear for the fate of the pastoral industry. This industry has a record of being able to adapt to change. One cannot blame its leaders for remaining sensitive to market signals.

The land deserves a more intimate and loving human connection than what is currently on offer in many situations. Without radical change, I now fear for remote townships and rural communities. Yet it is in many instances supposedly “unviable communities” that allow individuals a closer bonding to the continent that is our home. It is therefore in the interest of members of such communities to do their part in producing the sort of market signals that would empower individual industry players to safely explore regenerative practices.

I will not live long enough to see a full turn-around from ‘net soil loss’ to ‘net soilbuilding’, not on Kachana, let alone across northern Australia. Yet there is comfort in the knowledge that ‘net soilbuilding’ has been demonstrated to be a viable option.

All it would take is for existing experience and knowledge within the pastoral industry to be incentivized by informed consumer demand and environmentally literate leaders.

Pastoralism already offers by far the greatest level of hands-on custodianship in Australia’s landscapes.

Has the time come to redefine the goal posts?

History teaches us that pastoral exports contributed to making Australia a nation that enjoyed some of the highest standards of living in the world. It was my good fortune to have been in a position to experience some of that. What excites me today is knowing that this same industry could be pivotal in providing meaningful and rewarding opportunities to generations who might otherwise be plagued by climate-chaos related challenges.

Related links:

- A ‘Gym Approach’ offers safe learning 2020

- We have a broken global air conditioner 2020

- Presentation to Kimberley Fire Institute 2020

- Topping up carbon-accounts (updated 19 Mar 2020)

- Natural Capitalism and an Economy Driven by Sunshine 2020

- Reinventing Landscape-Management through Regenerative Pastoral Practices 2019

- Pastoralists to the rescue – Part 1. New Millennium, New Challenges 2019

- Pastoralists to the rescue – Part 2. When Alarm Bells Ring 2019

- Kachana: A 750mm-rainfall desert 2018

- The New Megafauna – Key to future prosperity – with Chris Henggeler 2018

- Kachana back-story with Chris Henggeler at the homestead 2018

- WHY REHABILITATE DEGRADED RANGELANDS? Chris Henggeler, Hugh Pringle 2013