Fundamentals or innovations – which way would you go?

Host: Northern Beef Development project

Written by Mariah Maughan and Steph Coombes, Development Officers, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development

If you had the chance to make a low-risk investment of $15,000 to improve your business, what would you spend it on?

At first glance, many of us would consider that a simple question. “Easy, I’d use it on XYZ”. But when you stop and think about it, I’m sure the decision would become a little bit harder.

This is something almost 70 Pilbara and Kimberley pastoralists have had to consider over the past few years.

Back in 2015, the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development’s Northern Beef Development project implemented an incentive-based Business Improvement Grants (BIG) program. The program assists commercial cattle producers in the Kimberley and Pilbara pastoral regions enhance their competitiveness and growth prospects by connecting them with professional business advice and mentoring support.

The program reimburses approved applicants with up to $25,000 (excluding GST), including up to $10,000 to engage a consultant to review current performance and develop a business plan, and up to $15,000 to implement key business improvement strategies as identified in the business plan.

So what does that actually mean?

Businesses (stations) in the program are reimbursed to hire a consultant and review or make a business plan. From that business plan, they identify different business improvement strategies and can be reimbursed up to $15,000 to implement them.

The strategies have to be related to the business plan. If the business plan identifies that opening up new country is integral to the business development strategy, and then asks for the $15,000 to be applied toward genetic testing …that probably wouldn’t be approved. But if a business plan which identified opening up new country as a priority, and asked to have the money applied toward drilling a bore – then most possibly yes!

Forty-eight pastoral enterprises participated in the initial round of BIG, utilising the grant in a range of business improvement areas. In 2018 an additional 20 enterprises joined the second round of the program.

So, how did these pastoralists spend the money? Read below for a few examples (and a video!)

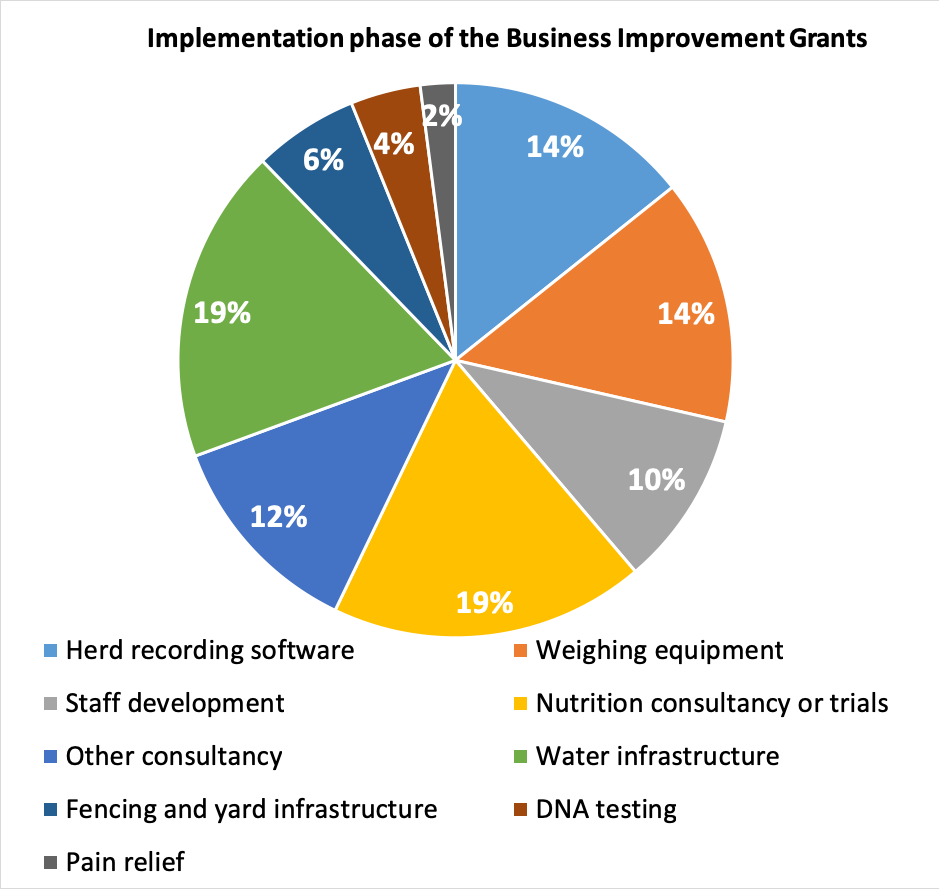

Figure 1: Focus areas of business improvement activities.

Figure 1: Focus areas of business improvement activities.

Data recording

The extensive production systems in northern Western Australia can see pastoral enterprises manage anywhere from 1,000 to 80,000 head on parcels of land sized up to and more than 400,000 hectares.

Terrain, mustering method and the sheer size of these cattle stations mean that achieving clean musters is a challenge and some animals may not pass through the yards each year, resulting in inaccurate livestock numbers. While traditional methods, such as a bangtail muster, can provide the opportunity to identify previously mustered livestock, they do not allow pastoralists to retain additional information on individual animals.

Through linking an electronic identification (EID) tag to herd recording software, pastoralists can build a history on individual animals, providing invaluable data on both cattle and business performance. Data collected may include age, weight, body condition, pregnancy status, wet/dry status, and vaccination history. Weight recording can be used to assist pastoralists drafting lines of cattle by weight class, as well as those wishing to calculate average daily gains.

Some pastoralists in the BIG program invested in crush side hardware, including scales, an EID reader and a data box. Others opted for in-paddock recording systems such as walk-over-weighers.

Just a few hour’s drive from Carnarvon, Winning Station spans an expansive 300,000 hectares of beef grazing country. Station owner’s Kim and Aggie Forrester used the Business Improvement Grants program to monitor and minimise the weight loss of cattle before export, a project which is already yielding positive results for both the animals and for the business’s bottom line.

They took some time to share their experience with us:

“We run 2500 head of Charbray Brahman crossbred breeder cows which relates to around 4500 animals on the ground.

(Aggie) In 2013 we achieved organic certification which I think certainly gives us more markets for our cattle. At the moment it’s very difficult to beat the bull market but I think in years to come there will definitely be a place for organic beef in Australia and overseas and we’re ready for it.

(Kim) Overall the grants program has been of benefit to us. We found part one of the program – the business planning – with our consultant very good. We like to get a business plan done every five years to see how the business is going, so some assistance in following along that line of thinking was great.

We used the part two grant to purchase the Gallagher TSI hardware. This included the wand, touch board and scales. We are currently using it to monitor weight loss from the station to Muchea sale yards and how we may alter our management and nutritional practices to decrease our weight losses which is both of benefit to our business and cattle health. It is throwing up some interesting results on feeding cattle in the yards and what the best way of preparing cattle for travel may be.

We are currently looking into how we should feed our sale cattle before trucking. This means looking into whether we should feed them from 2-3 weeks to 2-3 days to find out which results in the least weight loss. We previously were sitting at 10 per cent weight loss but have been able to decrease this to 7 per cent through putting our sale cattle on feed (commercial pellet) for 7-10 days before trucking. It is still early days but a 5 per cent average weight loss is the ultimate goal for us so hopefully the Gallagher technology can help us monitor and achieve that result.

When choosing our hardware we chose to go with the Gallagher through the recommendations of other pastoralists who had used it. We are happy with the hardware and all its capabilities; however we believe the biggest limiting factor to any herd recording hardware is the knowledge in how to use it. When looking at different brands of hardware it’s important to have good customer support so that you can get the most out of it.

I think it’s important to do your herd recording thoroughly and routinely to get the most out of the technology. Overall the grant program was very beneficial as it has allowed us to purchase technology that can really improve our business.”

Kim and Aggie Forrester.

Kim and Aggie Forrester.

Water and fencing

The primary limiting factor of infrastructure development on pastoral leases in the Pilbara and Kimberley is the availability of, and access to, capital. While increases in corporate ownership are resulting in an injection of capital across the region, significant opportunities to open up previously ungrazed areas of the rangelands through the development of water points remain. Some BIG participants used grant funding to partially reimburse the cost of sinking a bore, installing solar panels and troughs and piping off existing water points.

Annabelle Coppin, of Yarrie Station, Marble Bar, installed a remote water monitoring camera at the water point located furthest from her homestead. This resulted in a significant efficiency, allowing her to reduce the 200km round trip she previously travelled every five days, to now once every three to four weeks.

The installation of new fencing by other participants allowed for the resting of rangelands and cattle segregation, as well as developing laneways to assist with mustering and yarding up.

Focus on fundamentals or venture into innovation?

The awesome thing about the BIG program is that is provides pastoralists the opportunity to pursue a low-risk investment to trial a new business improvement strategy. It also offers them the freedom of choice as to what to apply the money toward (although it must be approved by the department).

Some pastoralists trialled innovative new technologies while others invested in fundamental business improvement practices. Investment choices reflected a number of factors, including the developmental stage of the enterprise, the risk profile of the pastoralist and the guidance of their consultant. For some pastoralists, new technologies to improve efficiencies were considered to be the greatest return on investment while for others, it was opening up new country.

I don’t think there’s a single place in the Pilbara or Kimberley, or northern Australia, that is 100 per cent developed with regards to infrastructure. Theoretically, every participant could have applied their grant money to waters or fencing – but not all of them did, and that’s what makes this program so interesting.

I mean, how often do we sit down and really crunch the numbers? What is going to give you the best bang for your buck? How much money is Annabelle saving in labour, diesel, and vehicle wear and tear, by cutting down that bore run?

The idea behind using consultants was to assist pastoralists in asking and answering these sorts of questions. This is also where the concept of the low-risk investment comes in.

There are new technologies being developed all the time, but many of us are hesitant to sink our money into them until they’re well and truly proven.

Participant feedback indicated that as a result of the consultation process, their reimbursement was applied toward a different strategy than the one they had originally envisioned.

The value of taking the time to plan and review business operations, as opposed to purely working init, has been a major outcome of the program. In an occupation where business owners and managers are required to possess an extensive skill set, the use of external consultants and mentors has been invaluable, planting the seed for paradigm shifts in pastoral operations.

The BIG program has proven to be a catalyst for intra-industry engagement, delivering the pre-conditions to drive transformational change and a conduit for information flow to and from industry. The high level of participation in the program is a testament to pastoralists’ ability to embrace change and new ideas – ultimately enhancing their resilience, adaptability and competitiveness.

BIG participant Annabelle Coppin inspects a remote water monitoring camera.

BIG participant Annabelle Coppin inspects a remote water monitoring camera.

A remote water monitoring camera on Yarrie Station.

A remote water monitoring camera on Yarrie Station.

BIG participant Annabelle Coppin inspects a remote water point from her Yarrie Station homestead.

BIG participant Annabelle Coppin inspects a remote water point from her Yarrie Station homestead.