Kachana: A 750mm-rainfall desert!

Host: Kachana Station

Written by Chris Henggeler, Owner.

“What do you intend on doing with that pile of rocks?” Back then Dad could appreciate the rugged scenery and the good water, but his question at the time remains a reality check to this day. Kachana Rock-Eaters, whose bodies were shaped more like those of grey-hounds than cattle, were far from a pretty sight to behold. This was September 1985.

Spinifex, rocks and WATER!

Spinifex, rocks and WATER!

We were not about to throw all our eggs into one basket. We were looking for something small, run down or even part of a station. Kachana ticked all three boxes. This was however, not the sort of proposition to sell to overseas business partners. “Gents, you will need to see this one for yourselves and then make up your own minds.” After a nine-day walk together in May 1986, one opted out, one stayed in!

What other boxes could we tick?

- Self-sufficiency potential and a small herd

- A rural setting for children to raise our children

- Close enough to town to facilitate off-farm income

- Tourism potential (to subsidise the necessary land-regeneration)

- Sunshine, rainfall and eroding land that nobody wanted…

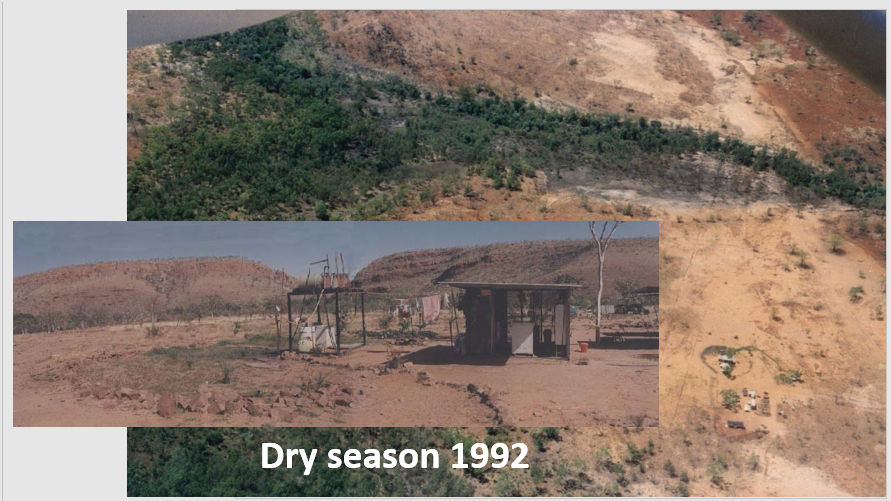

Our home in 1992.

Our home in 1992.

What else would you ask for when you are young and bullet-proof? Local experience and cash, of course! But surely, we could pick these up along the way if we applied ourselves, remained observant and persistent?

Working on stations in the NT and in Queensland had been time well spent. Casual work on farms in NSW and Victoria had also given me some insight to Australian landscapes and seasons. But little did we know about what lay ahead.

We were not the only ones to be cut down to size by high interest rates and a crumbling Aussie Dollar versus a Swiss Franc loan. Having no road access was a challenge that could be overcome. The big shock came when we realised that the few spots that actually did have pastoral potential were experiencing an accelerating ecological downward spiral. Wetlands were draining and drying out, creek-banks were disappearing, and sheet-erosion was the norm. Local native animal populations were in decline.

In the early days we very seldom saw any wildlife.

In the early days we very seldom saw any wildlife.

We applied conventional wisdom: culled donkeys and destocked cattle. With some high-rainfall years things got worse. We soon found ourselves trapped in a three-year wild-fire cycle and there was no sign of the learning-curve slackening off. We believed that the answers lay somewhere out there in the landscape. We tried things we had seen work in other parts of the world. Nature proved to be a hard, but fair teacher. By 1997 we were beginning to get some encouraging results.

Top: Kachana Photo Monitor Site No. 2.: Before and after.

Top: Kachana Photo Monitor Site No. 2.: Before and after.

Bottom: Bare ground, compaction and overgrazing – formerly feral stock now working as a herd – we use them to mulch, evenly fertilise and to prune plants – fresh growth allows more energy to be captured; when the “tap” shuts off we end up with standing hay for the dry season.

It was time to go back to school. We needed to better understand what the land was telling us. An initiative that had ministerial support at the time brought “new thinking” to the region. Anybody who has ever attentively attended a Grazing for Profit School will go back home and look at the land, livestock and business in a new way. Some then adjust the way they do things, others wait until for them the time is right to change… each manager, each station, each business, and each family remain unique.

For us on Kachana the time was right. We could begin answering unanswered questions, and we were able to more effectively source other missing knowledge and skills. Then with the advent of the internet to Kimberley stations (2001) we were able to compare notes with pastoralists and farmers in other regions and on other continents who were facing similar challenges.

Our home in 2015. With the use electric fencing we create a mosaic of grazed areas. This allows other species to do their thing too. (Each species has a role to play. We do not know what birds, lizards, mice etc. all do, but if they are not there, they certainly cannot be doing what they could be doing.)

Our home in 2015. With the use electric fencing we create a mosaic of grazed areas. This allows other species to do their thing too. (Each species has a role to play. We do not know what birds, lizards, mice etc. all do, but if they are not there, they certainly cannot be doing what they could be doing.)

The learning has taken longer than anticipated, but we now have sufficient local knowledge as well as the biological foundations on which to build multiple independently viable land-based enterprises. I remain inspired by a templet outlined by Joel Salatin, and see some great opportunities for life-affirming dynamic young people to dot Australian landscapes with viable regenerative enterprises. The good news is that science has caught up and none of us needs to reinvent the wheel.

I am now an old man looking at handing over the reins, but if Dad were to ask me the question again today, my answer would be the same: I’d like to build a small viable cattle enterprise that can sustainably export a few hundred head of quiet, genetically sound store cattle each year.

Meanwhile our rocks are slowly returning to become the water-reservoirs they might have been in earlier times…

Cockatoo Creek used to stop flowing each year and much of it dried out. Now it runs all year round and also supplies water for our camp.

Cockatoo Creek used to stop flowing each year and much of it dried out. Now it runs all year round and also supplies water for our camp.

The key for us was to let the large herbivores do the work. They are our gardeners. “Australia’s New Megafauna” is what we call them 😊.

Managing cow-power: Allowing for natural herd-instincts and animal-welfare, we comfortably and safely put cattle to work at high animal densities.

Managing cow-power: Allowing for natural herd-instincts and animal-welfare, we comfortably and safely put cattle to work at high animal densities.

You can learn more about Kachana Station by visiting their host profile here and their website here.