Lessons from a little cat

Host: Dampier Downs Station

Written by Anne Marie Huey – Manager, Dampier Downs Station.

When I said “No more puppies!” I did not expect to come home from town one day to find two tiny kittens installed in my kitchen. These little cats, one girl, one boy, had been abandoned by their mother and were found – of all places – in the dog run. Normally, Mike and I do not approve of feral cats as we are well aware of the environmental damage they wreak, but these guys were so small and so defenceless we had no option but to adopt them.

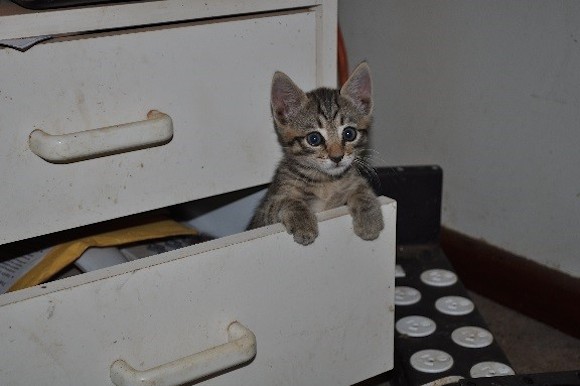

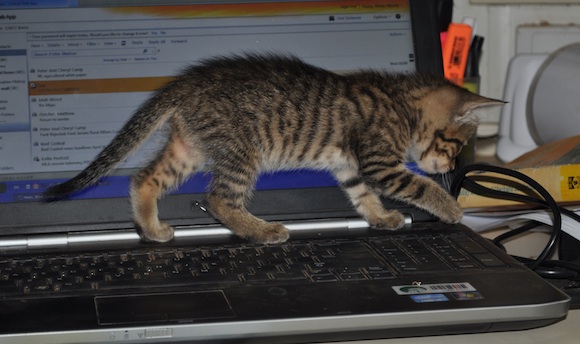

Bitty and Puddin when they were still determined to be wild.

Bitty and Puddin when they were still determined to be wild.

It took a couple of days and some serious bribery in the form of mince and milk, but eventually they came around and turned into two very loving, and very much-loved, family pets. They were moved from the kitchen to my office and began growing rapidly.

Being kittens, they were extremely playful and constantly looking for adventure. Before long, I felt they were rapidly outgrowing my office, but with so many dogs I could not let them out to explore during the day. My solution was to wait until all the working dogs had their final exercise and feed for the night and were securely locked in their pens and the pet dogs were also chained up for the night, then I would let them out for a couple of hours in the evening to broaden their horizons. This worked really well until one night it didn’t.

Bitty, the little girl, did not come in for her dinner. By about nine o’clock I was really worried so began searching for her. Eventually I found her curled up in a spare wheel in front of the workshop. The minute I picked her up she began to purr loudly and I thought we had dodged a bullet. I took her back to my office and put her down in front of her food bowl and that was when I realised something was terribly, dreadfully wrong. It was like the left side of her body had no power and she could not stand up. She wasn’t paralysed as she could still move her legs, but nevertheless something was seriously wrong. I put her into her bed, cleaned her up and that was when I noticed puncture wounds on her back leg. I could only surmise a dingo had been skulking around the workshop and got hold of her. I hand fed her a few morsels of mince, tried to get her to drink some water and sat with her, purring all the while, until she fell asleep.

At six o’clock next morning I carefully placed her in the car and set off on the three and a half hour trip to town to take her to the vet. We hadn’t had her long but she had firmly cemented a place in our hearts and I was determined to give her every chance at survival.

Unfortunately, after an examination by the vet it was determined her injuries were just too great and the kindest thing was to put her down. Of course, I was devastated but the end, when it came, was peaceful and incredibly quick. Then, there was nothing else to do but put myself back together and get on with the three and half hour drive home.

I always finding driving is a great time for reflection and that day was no exception. I began asking myself if taking Bitty to the vet was really in her best interest, or mine? If I were to be brutally honest, I probably knew the night before that she couldn’t be saved, but I also know I would have always had that niggling doubt and associated guilt if I hadn’t tried. So, was my ‘act of kindness’ really the right thing to do, or would a quick end twelve hours earlier have been better for Bitty? Either way, my conscience is not entirely clear but I can at least console myself with the knowledge that though Bitty’s life was short, it was happy and filled with love.

I then began thinking about how this experience contrasts with some of the standard animal husbandry practices we routinely carry out on our cattle. In particular, how some of our procedures can look inherently cruel on the surface, but when you start to examine the motivations behind them, they are in fact the kindest things to do.

Take, for example, dehorning. It is a bloody business that undoubtedly causes pain at the time. The calves bellow and it is not a pretty sight to see blood spurting from the heads as they leave the cradle. However, on the flip-side, I have seen old cows come into the yards with misshaped horns growing into the side of their heads or, even more horrifically, into their eyes. I have seen animals in agony that had to be destroyed after being gored by a bull and personally know at least three people who are extremely lucky to be alive today after run-ins with wild bulls.

I have also seen weaners settling in to munch on a pile of fresh hay and calves happily head-butting mum in the belly to get her to let down some milk mere minutes after being dehorned. This indicates to me that far from suffering an extended period of trauma after dehorning, recovery begins almost immediately.

So, while dehorning may appear cruel, would banning it (as some animal rights groups advocate) really be in the best interest of the animals and people who work with them, or would it simply serve to assuage the conscience of a largely uninformed public who will never have to deal the unintended consequences of such a policy?

I guess the message I am trying to get across is that even the best intentioned actions can cause unnecessary suffering, and actions that may appear callous on the surface can actually result in a long-term benefit. It is my hope that next time you hear about a farming practice that is considered cruel or inhumane, or are asked to sign a petition or boycott a certain product, dig a little deeper. Ask questions of people on both sides of the argument. It may end up that you still disagree with a certain practice but at least you will be making an informed decision.

And when you get home tonight give your pet – cat, dog, or guinea pig – an extra pat from me.

RIP Bitty.