Not all were created equal

Host: Katherine Research Station

Written by Jodie Ward – Pastoral Production Officer, Department of Primary Industry and Fisheries, Katherine Research Station.

If there was a cow in your herd that was consuming resources, but not giving you anything back, you’d get rid of her wouldn’t you? Especially, if she came through the yards, year in, year out, eating all the grass but without any calves at foot.

Hi I’m Jodie Ward and I’m a Pastoral Production Officer with the NT Department of Primary Industry and Fisheries.

Hi I’m Jodie Ward and I’m a Pastoral Production Officer with the NT Department of Primary Industry and Fisheries.

The same could be said for increaser pasture species. These species are the ones that cattle graze around. They eat the softer foliage off the bottom, but that is all. They might eat them when they are lush and green in the early wet season, but as soon as the rain decreases and they set seed, cattle avoid them like the plague.

Maybe the plant is too “stemmy” – too much stem compared to the amount of leaf. Maybe the plant smells funny. Maybe the plant is too hairy and feels funny going down the throat of the animal or causes ulcers on the gums. Either way, once it sets seed, there is nothing to reduce its competitiveness. While all the other desirable plants around it are being grazed these increaser species just mosey on in, picking up the available bare soil when the desirable species have been grazed out. An example of such a species is Aristida latifolia also known as Feathertop wiregrass, or White speargrass.

Feathertop wiregrass (Aristida latifolia) is a prime example of an increaser species.

Feathertop wiregrass (Aristida latifolia) is a prime example of an increaser species.

There are some examples of areas on the Barkly and also in the Victoria River District from historical grazing pressure back in the early days of pastoralism in the NT before fences were created. Early pastoralists were aware that cattle never travel too far from water, so they had the rationale that as long as there was a billabong or a watering hole, the cattle wouldn’t be too far from it.

As you can imagine, over a sustained period of time, as men left the area to join the war effort, with little way of controlling the breeding program, the herd got a little out of control and the area became overgrazed, removing the Astrebla (aka Mitchell grass) from the landscape. As a result of this, some of these areas now feature a near monoculture of Aristida. As you can imagine, having a vast area of not much more than an undesirable increaser species has to be managed very carefully to ensure it has some grazing value to the cattle and the few desirable species that are present are not grazed out.

My absolutely favourite pasture species, Dichanthium fecundum, more commonly known as Curly bluegrass. Just look at it, isn’t it just heavenly?

My absolutely favourite pasture species, Dichanthium fecundum, more commonly known as Curly bluegrass. Just look at it, isn’t it just heavenly?

While the Aristida species are playing a role in the ecosystem, such as holding the soil together as it is a perennial (lasting more than one year) and providing shelter to wildlife, I ask, wouldn’t it be better if it was a species that we could use for beef production as well? Such as any of the native Astrebla species?

Wouldn’t it be better if we didn’t have to implement costly infrastructure developments just to ensure that cattle will graze it purely because there is nothing else on offer?

Wouldn’t it be better if we knew enough about our local native species and their grazing tolerances so we could prevent this from occurring in the first place?

The beautiful Barkly and some curious heifers.

The beautiful Barkly and some curious heifers.

I say yes. I say that not all pasture species were created equally. Not all are desirable and if you have mostly undesirable species, you need to do something about it.

Suggestion 1: get to know your species. Knowing which are good and which are bad is the key.

In the NT, the pasture identification books we particularly like include:

“Pasture plants of north-west Queensland “, by Jenny Milson

“Plants of the Barkly Region, Northern Territory”, by Jenny Purdie, Chris Materne and Andrew Bubb

“Grasses of the Northern Territory savannas: a field guide”, by Sam Crowder and Boronia Saggers

“Plants of the Kimberley Region of Western Australia”, by R.J Petheram and B. Kok

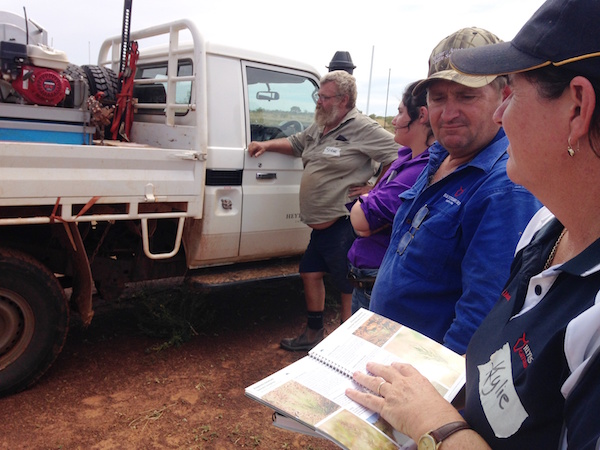

Getting amongst it: Kylie and Lance Hutley, Managers of Birrundudu Station, working out what is what earlier this year at a Rangeland Management Course.

Getting amongst it: Kylie and Lance Hutley, Managers of Birrundudu Station, working out what is what earlier this year at a Rangeland Management Course.

Suggestion 2: Reduce stocking rate to closer to that of your long term carrying capacity. By reducing the numbers of grazing mouths in the paddock will relieve the grazing pressure on the plant species. This will give the genuine, desirable, productive, perennial pastures a fighting chance.

Suggestion 3: Provide a wet season spell next year. Do not reintroduce cattle until all plants have set seed and become dormant.

Suggestion 4: Control your weeds – they are nothing but no-good-dirty-rotten-nutrient-stealing wastes of space. Something good could be using those nutrients instead.

Suggestion 5: Know if your undesirable plant species thrives or declines if burnt. Some do, some don’t, it’s worth investigating. You may need to remove stock to ensure there is enough fuel to carry out the heat desired to retard it.

Suggestion 6: Contact your local Department of Primary Industry and Fisheries (or relevant department in your state) Officer and they will be able to help you out.

It’s all interrelated!

It’s all interrelated!

So in conclusion, I hope I have passed on to you my passion for native pasture plants, and hope that I have inspired you to go have a look around your paddocks. And just remember – not all were created equal.