Pastoralists to the rescue – Part 2

Host: Kachana Station

Written by Chris Henggeler, Owner – Kachana Station

Part 1. New Millennium, New Challenges

Part 2. When Alarm Bells Ring

A nurse or doctor can hand out medication and check up on a patient on their own, but when alarms begin to go off in a hospital ward, it is useful to have a team that understands the challenges and that will come together as the situation demands.

Watching the news in a year like 2019 is a good reminder that fires, droughts and floods are a community issue. Running a business on land can be reduced to single enterprises or individual levels. On the other hand, drought-proofing, flood-proofing and fire-proofing entire landscapes requires ecological doctoring at a grand scale and in a coordinated fashion. Challenges like these that do not respect regulations let alone property borders, and demand support from community and government.

Once country has been written off by the pastoral industry (and people do vote with their dollars!), it is a little like when a patient has been left to die. Life-support is switched off, alarms no longer get activated, and there is no longer the need for a team. People on the team have other cases to attend to.

Hence, when nature sounds an alarm in the rangelands, often there is nobody there to hear it go off.

For us on Kachana, this has its advantages. Not every mistake that we have made in the last 30 years is officially registered. When we get bucked off, we shake the dust off, lick our wounds and get back into the saddle.

When we get it wrong Nature will tell us. E.g. Fibre-glass spacers proved to be a bad idea for the particular job that we had in mind.

When we get it wrong Nature will tell us. E.g. Fibre-glass spacers proved to be a bad idea for the particular job that we had in mind.

There is a down-side to such isolation. Sometimes there is real trouble. There have been three notable occasions when nature sounded an alarm and on each it would have been good if others beyond Kachana would have paid attention.

The first was in October 1996. A fire raged through an area of well over 6000 square kilometres (including Kachana’s 775 sq km). Twenty-three years later, from what we can tell, not a single affected area has fully recovered.

The second was early 2001 when the Salmond River self-destructed. The Durack River got some attention because of infrastructure lost at what formerly was Jack’s Hole. But what was occurring in the Salmond catchment remained ‘out of sight, out of mind’.

The third time was March 2011 when the Chamberlain River sounded an alarm. At the same time, some kilometres to the East, smaller alarm bells did gain attention: a creek that few would have even heard about, made national headlines. Band-aid measures were urgently required and the township of Warmun had to be rebuilt. Teams responded and (if I am correctly informed) over 200 million dollars later, the “patient” lives. The “patient” is now in a condition which the medical profession would term “critical, but stable”. The actual cause of the flood was neither recognised nor dealt with, but life in the township is back to what people consider normal.

The Chamberlain River, meanwhile was ignored and has been since forgotten.

The Chamberlain River, meanwhile was ignored and has been since forgotten.

Living in a location perched in the catchments where such floods originate, we get the grandstand view not only of what happens during such events, but also of the lead-up and later we get to observe the flow-on effects. With the help of what others have drawn our attention to, we do our maths and realise it is not about the amount of rain! Floods result from ineffective water-cycles. The challenge is not only the management of production-areas, but also custodianship in the areas beyond. (Click hereto find certain aspects of the water-cycle explained in a slide show.)

We were confronted with options. Do we manage the land to merely justify our investment or do we manage the land in a way that it will heal and regain former or even higher levels of productivity?

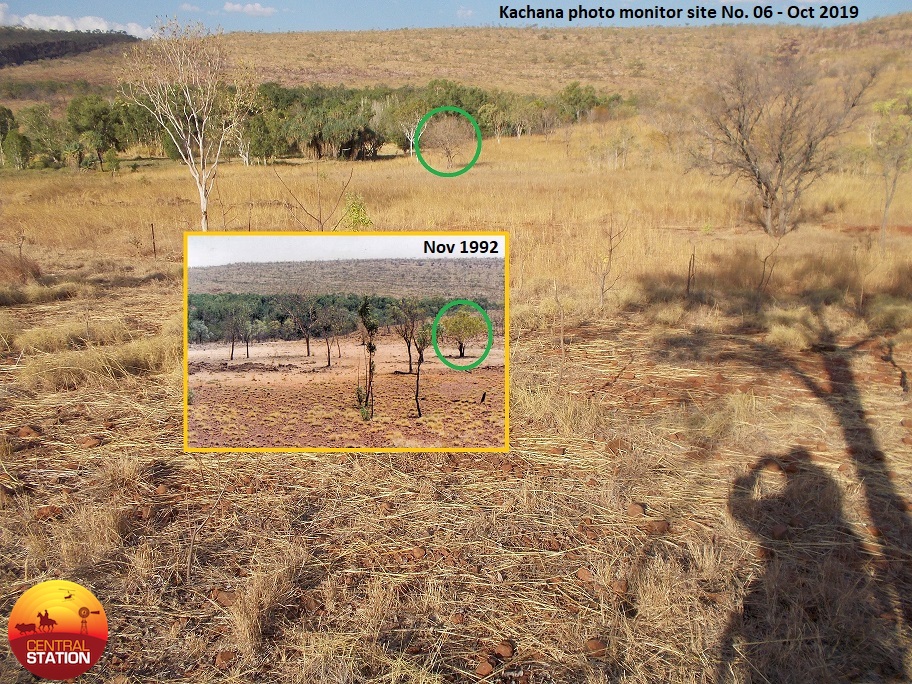

Our choice was influenced by encouraging results we were observing as the country responded to managed large herbivores and less fire.

Our choice was influenced by encouraging results we were observing as the country responded to managed large herbivores and less fire.

We do not own the land, but we do our best to deserve managerial entitlement. This means we need to demonstrate a type of custodianship that benefits the community at large. For dealing with degraded areas, we have a simple four-step approach: first-aid; intensive care; rehab; production.

We decided to stick to the multigenerational perspective. In this particular case we continued to subsidise our efforts with various streams of off-farm income. The choice was not an easy one, because incentives are few and in our case politics added a further dimension. We had found a use for “feral animals” and we were putting them to work.

Our donkey project has now been on hold since 2017, and politics in this instance has served to keep me more in the office than out in the field where I would much rather be. But it was in the office that I discovered that during the thirty odd years that we had been experimenting on Kachana, others too had been experimenting. More so, the science was now fast catching up and ideas that only twenty years ago were being attributed to “the lunatic fringe” are now being taken seriously in many parts of the world. More mouths and more demands place increasing strain on finite resources and water is fast being recognised as becoming one of them.

At industry levels, a pastoral manger not only needs to know about business, accounting, finance, marketing, animal-health, OH&S and politics, she/he invariably also find themselves to be somewhere along a journey from horseman – cattleman – stockman – grass farmer – soil builder – rainfall manager to custodian.

(Unsurprisingly, she/he is never permitted to be grumpy or frustrated! 😊)

Beyond the boundaries of conventionally viable industry practices, this same journey opens up a whole range of new opportunities. (At least I hope so; I have a lot of money on that bet!)

A look at history and I see: fat grasslands – fat cattle – fat profits – fat wallets. Of course, there was no lack of blood, sweat and tears and my respect for those who went before me deepens as I learn. In these past forty years I’ve seen timing, work and skill also produce fat wallets, but rather than building soils, Australia appears to have experienced a net loss of soil (i.e. loss of life in soils and subsequent erosion).

In some places this loss of soil may have been triggered sooner and has perhaps moved along faster. I look at my 750mm rainfall desert and I see a “well boned out carcase” of a landscape.

In some places this loss of soil may have been triggered sooner and has perhaps moved along faster. I look at my 750mm rainfall desert and I see a “well boned out carcase” of a landscape.

With what we know today this should be an opportunity: There is sunshine, rainfall and rock (right down to the size of sand, silt and clays). We have on-site nature’s basic ingredients to rebuild healthy savannahs, forests and wetlands. We can reverse the undesirable direction of current processes to rebuild former or even higher levels of productivity: “fat” soils, “fat” vegetation, and eventually fat animals and sustainable profits. Well hydrated landscapes are the basis for biodiversity and therefore natural and agricultural wealth.

Given our latitude and rainfall, there is the potential for ‘high performance landscapes’!

High performance athletes are not just born that way; in order to excel they need to be nurtured and to train strategically as well as hard. It is no different for human-shaped landscapes in Australia and in other parts of the world. If we wish for landscapes to become healthy and to excel, it requires vision, appropriate nurturing and management. We call that custodianship.

We thus aim to hang on to more water each year and in turn grow more healthy vegetation. From above, plants pull in energy and carbon with which they supply the underground workers. Plants as they mature then also provide a surplus for herbivores and omnivores.

If soils are all but lost and bed-rock begins to appear, much hard work and energy are required to build or rebuild healthy, productive landscapes. Good news is that we can go about it in a manner that leaves all the heavy lifting to biology. Therefore, if it is alive, we do our best to give it a job.

(N.B. When biology does the work, the situation is scale-neutral. Meaning: the size of the area no longer matters, the same processes are at work whether we look at a single hectare, a catchment, a property or a whole region.)

On Kachana we delegate to Middle Level Management. We see our large herbivores to be the plumbing, electrical and gardening contractors!

Plants we see to be our Lower Level Management; Plants communicate!

A healthy plant tells us: The management that is taking place here suits me just fine!

An unhealthy plant tells us: There are things happening here that I feel uncomfortable with…

The role of a functional working herd is to mulch, evenly fertilise and prune vegetation.

In a production situation we do well to bear in mind:

- If we get the herding right, but the timing wrong, we will kill our profits and our animals with no harm done to the land!

- If we get the herding wrong, we risk allowing the animals to mine nutrients out of the landscape whilst triggering a range of undesirable trends. Much cash-flow can be generated while the land deteriorates.

- Animals do not put on weight whilst looking for feed or while walking to and from water; they put on condition whilst sleeping and when chewing their cud (if they are ruminants).

- Therefore, the free solar energy that is used up each day while animals are foraging and moving to and from water, (if harnessed) may be used to provide regenerative outcomes

Healthy plants feed the life in our soils. It is the biology in our soils that assists in rehydrating landscapes and thus addressing the challenges of flood-mitigation and drought-proofing. Wild-fire mitigation strategies then vary from place to place and from season to season.

We use what is currently labelled as the “destructive behaviour of large herbivores” to strategically create low fuel zones. We simply give them longer access to an area. In the picture above (to the right of the temporary electric fence) you see the work of wild donkeys and a few head of cattle.

We use what is currently labelled as the “destructive behaviour of large herbivores” to strategically create low fuel zones. We simply give them longer access to an area. In the picture above (to the right of the temporary electric fence) you see the work of wild donkeys and a few head of cattle.

We’d rather see vegetation cycled through herbivores than have it go up in smoke and leave soils exposed. Bare ground is soil that has had its skin ripped off. As with burn-patients, it is the dehydration that kills.

We’d rather see vegetation cycled through herbivores than have it go up in smoke and leave soils exposed. Bare ground is soil that has had its skin ripped off. As with burn-patients, it is the dehydration that kills.

Healthier vegetation is more readily converted to ground-cover and good body-condition in our animals. This of course is CO2 DRAWDOWN!

Healthier vegetation is more readily converted to ground-cover and good body-condition in our animals. This of course is CO2 DRAWDOWN!

Large herbivores (in our case donkeys, horses and cattle) are often also severe grazers and tramplers. (The larger the herbivore, the more “rubbish plants” it can re-cycle or even up-cycle.)

We have observed that managed large herbivores can be used to complement and even perform the beneficial role that fire might perform in a landscape: create edge-effect and remove dead and senescent vegetation which might otherwise choke new growth.

More importantly, appropriately managed large herbivores do not produce the negative effects that so often come with fire.

(i.e. Fire exposes soil, pollutes the air and dehydrates bare ground that is then exposed to further dehydration and erosion. – Apparently fires “burp and fart” more methane than ruminants do. Furthermore, healthy soils absorb more methane/ha than the large animals can provide.)

When managed so as to work in accordance with the functional roles of their wild ancestors, large severe grazers also make life pleasant for nibbler-species. In our case we have a range of marsupials who come and enjoy the fresh sprouts which begin to appear within days after biological mowing by the severe grazers has taken place. Commercial producers may choose to add more species to their enterprise-mix.

I remain deeply thankful to the many individuals who over the years assisted me to understand and to formulate what I see to be an inspiring message to those who love the land:

- In rangeland Australia our most powerful tool is the behaviour of our “NEW megafauna”

- Producing high-quality animals is what pays wages today

- Skills required to do so in an ever-changing world are constantly evolving

- A basic skill-set required for broad-scale ecological doctoring already exists within the pastoral industry

- Working with such skills is already proving to be profitable

- In other parts of the world ‘herding schools’ are now training ecological doctors

- Once the incentives appear, so will the Aussie Land-Doctors

In conclusion: Revitalising a prairie or alpine pasture which has been dormant or even “comatose” for a century or three is one thing.

Regenerating landscapes that were compromised by the disappearance of Australia’s Old Megafauna takes the challenge to new levels.

However, we know how to harness the energy of Australia’s New Megafauna to begin the task! Demand for this ‘working knowledge’ which already exists within the pastoral industry will grow in Australia and in other dry regions of the world.

- Rehydrated landscapes are more resilient in the face of drought, flood and fire.

- Rehydrating landscapes offers water-security and hence genuine biosecurity!

- Rehydrating landscapes is a community-building activity.

- Hydrated, functional landscapes are biodiverse and resilient. They represent the sort of wealth that supports communities and nations.

Pastoralists to the rescue! – Aussie Aussie Aussie, oi oi oi!

List of links relating to the message above:

Related reading:

- ‘Defending Beef’ by Nicolette Hahn Niman

- ‘Cows Save the Planet’ by Judith Schwartz

- ‘Water in Plain Sight’ by Judith Schwartz