The Ring of Fire

Host: Dr. Ross Ainsworth

The imminent eruption of the Mt Agung volcano in Bali is not just a serious threat to the local population and a significant humbug for tourist flight schedules, it is an important example of how vulnerable Indonesia is to the very serious geological threats presented by both earthquakes and volcanic events. With so much of the Australian livestock trade dependent on Indonesia, it’s essential to understand the risks involved.

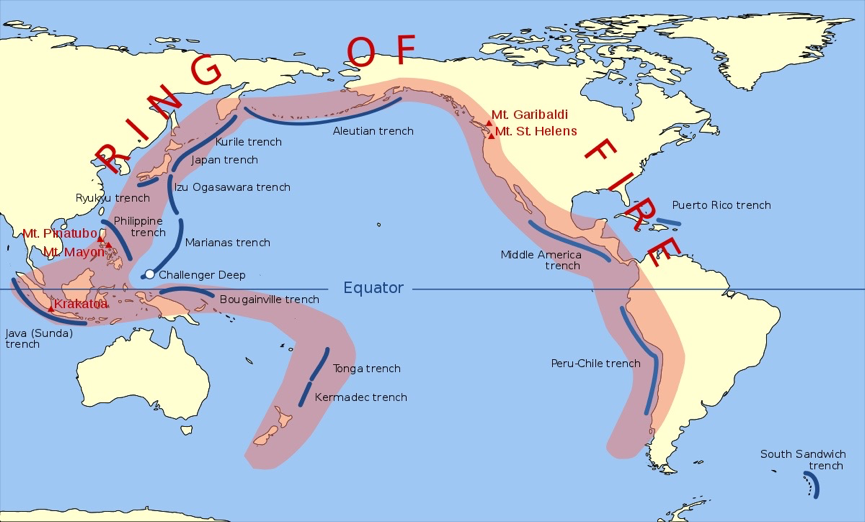

Indonesia forms a major part of the “Ring of Fire” shown in the two maps below.

The 452 volcanoes within the Pacific Ring of Fire represent about 75% of the world’s active and dormant volcanoes.

The 452 volcanoes within the Pacific Ring of Fire represent about 75% of the world’s active and dormant volcanoes.

The red triangles show Indonesia’s many active and dormant volcanoes.

The red triangles show Indonesia’s many active and dormant volcanoes.

About 90% of the world’s earthquakes occur along the Ring of Fire. The next most seismically active region is the Alpide belt, which extends from Java to the northern Atlantic Ocean via the Himalayas and southern Europe. Indonesia is sandwiched between these two seismic giants resulting in the islands experiencing some of the world’s strongest earthquakes and most powerful volcanic eruptions.

The risks that these volcanoes present to the nation of Indonesia are potentially catastrophic and probably outstrip any other form of potential national calamity including political, economic, military, or social events. As one of Australia’s nearest neighbours, there is always a chance that these events may be large enough to have a significant impact on Australia.

This famous photo from the internet shows the pyroclastic flow racing away from the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991. When the ash from this eruption reached Darwin in the Northern Territory it blocked out the natural daylight to the point that the Darwin street lights were automatically activated.

This famous photo from the internet shows the pyroclastic flow racing away from the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991. When the ash from this eruption reached Darwin in the Northern Territory it blocked out the natural daylight to the point that the Darwin street lights were automatically activated.

With a population of close to 200 million people squeezed into the two islands of Java and Sumatera along with a very large number of active volcanoes it seems that the area is very lucky that there have not been a lot more disastrous eruptions in recent times. Mount Merapi delivered the last major eruption in Java in 2010 when it resulted in massive loss of property and the death of 353 people. While these statistics represent a terrible loss, they don’t seem quite so great when you consider that more than four million people live in the city of Yogyakarta which is only about 30km from the summit of the Merapi. So much of the outcome from these events depends on the track that the lava and gases take as they flow down from the volcano as well as the direction of prevailing winds. If the direction of the wind and the pyroclastic flows had been towards the main population areas of Yogyakarta then the potential for human loss of life would have been catastrophic.

Photo from the internet : Damage from Mt Merapi in 2010. The loss and devastation is both immediate and ongoing for years afterwards as it takes communities and the environment a very long time to recover.

Photo from the internet : Damage from Mt Merapi in 2010. The loss and devastation is both immediate and ongoing for years afterwards as it takes communities and the environment a very long time to recover.

Krakatoa is a volcanic island situated in the Sunda Strait between the islands of Java and Sumatra. The original volcanic peak was obliterated in the cataclysmic 1883 eruption, unleashing huge tsunamis killing more than 36,000 people and destroying over two-thirds of the island. The explosion is considered to be the loudest sound ever heard in modern history, with reports of it being heard 4,800 km away in Perth.

I took this photo of Anak Krakatoa (baby Krakatoa) during an active period in 2010. It is slowly growing up again out of the sea.

I took this photo of Anak Krakatoa (baby Krakatoa) during an active period in 2010. It is slowly growing up again out of the sea.

The Lake Toba volcano in north Sumatera erupted 75,000 years ago. Ice core records have shown that Toba was the largest volcanic blast in the last two million years.

I visited Lake Toba in 2013. The landmass on the top left is part of an island in the volcanic crater lake at the top of the mountain. This island is bigger than Singapore!

I visited Lake Toba in 2013. The landmass on the top left is part of an island in the volcanic crater lake at the top of the mountain. This island is bigger than Singapore!

The eruption of Mount Tambora on the island of Sumbawa (east of Bali) in 1815 was the largest in human recorded history. While the local and regional devastation was enormous, the greatest impact was felt in the northern hemisphere where the volcanic ash dispersed into the upper atmosphere blocking enough of the sun’s rays to result in a long volcanic winter or the “year without summer” across Europe and North America. Crop failures and livestock losses resulted in the worst famine of the 19th century. Perhaps future eruptions may direct their ash to the southern hemisphere where Australia may be the subject of an extended volcanic winter. The threat presented from this type of scenario is obviously small but never the less real.

Mount Tambora on the island of Sumbawa in 2016. Volcanic mountains don’t have to look threatening to contain massive future eruption risks.

Mount Tambora on the island of Sumbawa in 2016. Volcanic mountains don’t have to look threatening to contain massive future eruption risks.

Photo from the internet : Mount Bromo, 80km south of nine million people in Surabaya.

Photo from the internet : Mount Bromo, 80km south of nine million people in Surabaya.