Water is life

Written by David Pollock, Wooleen Station

Over the past 13 years our main objective on Wooleen has been resting the landscape from grazing as much as possible, in order to let it recover itself from historical overgrazing. I won’t go into that too much because we covered it in last years stories (Story: Watching the grass grow). Suffice to say that the landscape recovery is progressing, quickly after rain and slowly for the great majority of the time.

We are now at the stage where most of our efforts are going into building and adapting the infrastructure we need to take advantage of the recovered pasture, as well as manage it in a way that ensures that it continues to recover. Much of this has also been covered in last year’s stories. Till the cows come home, & Doggone Kangaroos.

So were going to jump ahead a bit and outline the plan for the future. I realise that it’s a bit sneaky to be talking about things I’m “gonna do” rather than things we’ve actually done, but we have been pretty good at sticking to the plan so far. I feel confident that we can be held accountable to do the things listed here. Most of them we’ve started anyway.

The major change to our management will be a shift from set stocking to rotational/rest-based grazing. We are already doing this and have been since 2006, but without the infrastructure to do it properly. We have addressed this deficiency by simply selling all of the cattle once they have done a circuit of the available infrastructure. This has meant that we have traded cattle rather than bred them. However, we didn’t believe that we had enough recovered sweet perennial pasture to support a full-time breeding herd anyway, so the infrastructure has been progressing at a comparable rate to the pasture. The money from cattle sales went into better infrastructure for the next lot of traded cattle. So far, so good.

More fencing and cattle yards are certainly needed, but these are things that just make management easier. The cattle will survive just fine without them, in fact they’d be pleased as punch if there were no fences and even fewer yards. But what they won’t survive without is water. Providing adequate water is the real challenge to a rest-based grazing model here.

This well has not been used for at least 40 years, but after removing 3.5m of silt, rocks and logs with our well bucket and concreting a new well collar its ready to go again.

This well has not been used for at least 40 years, but after removing 3.5m of silt, rocks and logs with our well bucket and concreting a new well collar its ready to go again.

While its not that difficult to find some underground water in our country, it is difficult to find enough water to the support large mobs of cattle associated with a rotational grazing model. Essentially a shift from set stocking to rotational grazing means that cattle who used to be spread out over a large area are now concentrated into a much smaller area. Before, there were perhaps 50 cattle per water point, in a rotational model, there could be 500.

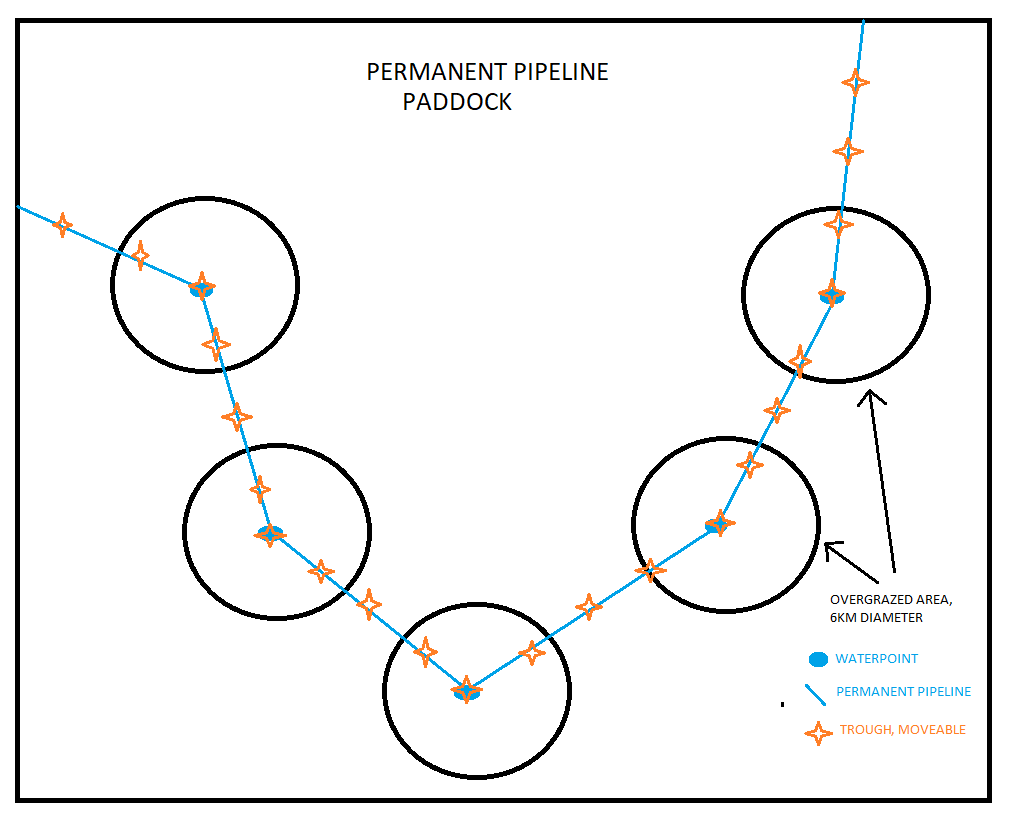

So, where do we get the water? Large Dams might help, at least for part of the cycle. Carting water is much too expensive. Connecting water points with pipelines so that the combined water of numerous points is available in one location is possible, but has significant drawbacks. Firstly, it would involve significant capital expenditure. Not only would the pipelines between waters be prohibitively expensive, but pumps would also be needed to pump over high points in the landscape between the waters, adding complexity. Aside from the cost there is another significant issue with this idea, an issue that affects our pastoral production more than any other factor that can be addressed in the short-medium term.

It is the distance that cattle walk from water to feed.

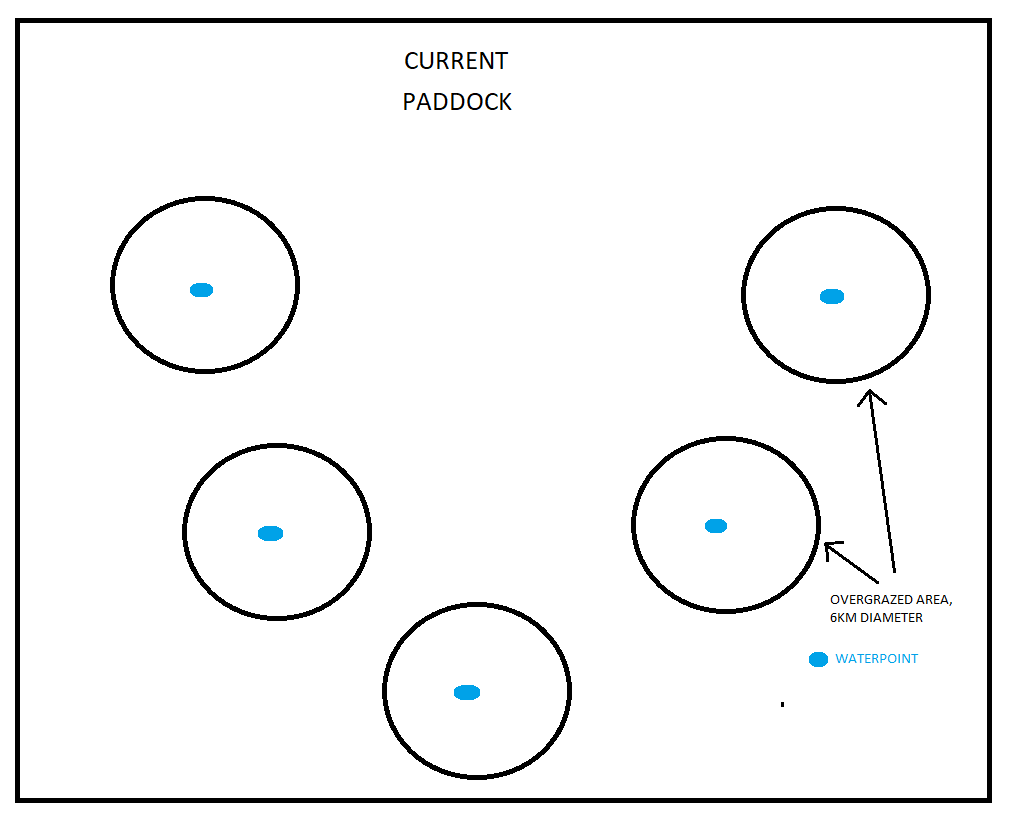

Existing waterpoints deliver very limited water to the least productive area.

Existing waterpoints deliver very limited water to the least productive area.

Historic overgrazing has resulted in most the good perennial feed within at least 3km of any permanent waterpoint to become severely depleted. This means that the cattle must walk long distances every day to get between the water and the remaining pasture, which causes them to lose weight. The drier it gets, the more this is true. As a beef business, we make money from cattle putting on weight. So the less they have to walk the better. If I was to connect all the waterpoints together, the cattle will still, for the most part, be drinking around the existing waterpoints, and therefor still walking long distances. Troughs would of course be added to the pipeline running between existing waterpoints, and these troughs would be in fresher pasture areas, but still a maximum amount of permanent pipeline would be within the degraded areas, and therefore not good value for money.

Pipelines connecting waterpoints to increase supply are not cost effective.

Pipelines connecting waterpoints to increase supply are not cost effective.

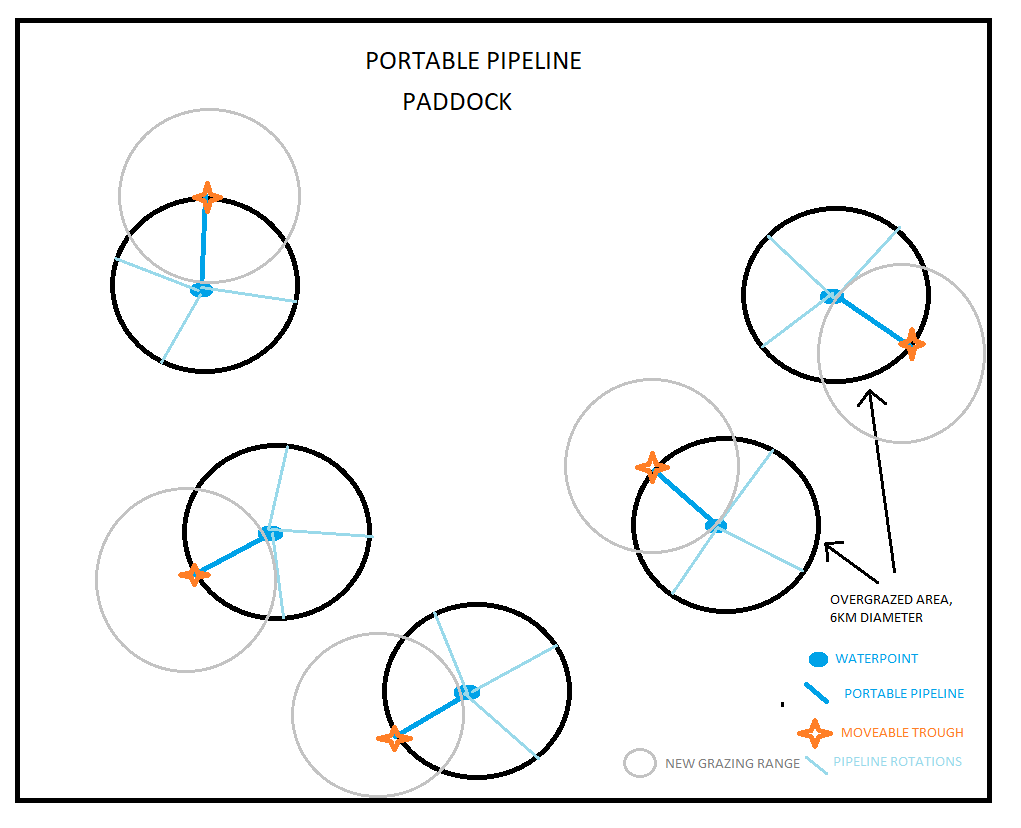

So, our plan is to build portable pipelines. Using trailer mounted ex-cable reels capable of holding 3km of 2” poly pipe, we can roll out 3km of pipeline away from existing waterpoints. This will significantly reduce the distance that cattle need to walk to water. Roughly every month, the pipeline will be moved to a different position on the “clock” that forms the radius around the waterpoint. This means that production will increase on a per head basis, as cattle will gain weight quicker because they will be watering in closer proximity to the feed. The moving of the trough around the “clock” will itself be a form of rotational grazing.

Portable pipelines maximise benefit from capital expenditure and increase productivity.

Portable pipelines maximise benefit from capital expenditure and increase productivity.

In addition to these small movements, we are creating paddocks of around 18,000ha that contain 5-8 permanent waterpoints. The cattle will also be rotated through these larger paddocks. Initially, the herd will spend 3-4 months in each paddock, drinking from a newly located trough every month. This is the basis for our rest-based grazing plan. But so far we have only addressed one issue, the distance that cattle have to walk to water. The other issue is how do we find enough water in one place?

Initially, our herd size will be limited to the available water. While we don’t often have good supply at any particular water, at least we know there is water there. Why not drill another bore? Our water exists in underground streams, rather than an aquifer, so if a new bore is drilled 20m away from the first bore or well, it’s unlikely to affect the original waters supply. This will double the water available at that site. As the intensively of rotational grazing increases, drill another bore. Eventually, instead of using all of the paddocks 5-8 waterpoints at any one time, there may be 5-8 bores being used at only one waterpoint.

At this stage all the portable pipelines might radiate out from the same waterpoint. Under this system, assuming that the whole herd (about 500 head) stays at any one water for a month, it would take a little over 3 years (40 existing waterpoints X one month each) to rotate around our existing waters. This system does not include paddocks for fattening and weaning, which are our most productive paddocks. It might sound a little fanciful because nothing pastoral progresses so simply, for example every time there is a significant rain event the animals would move out to the far corners of the paddock to make use of fresher feed and the good water afforded by puddles. This would undoubtably disrupt a regular rotation schedule. But good rains are a good problem to have!

Portable solar pumps, made from wrecked station trailers and general repurposed steel.

Portable solar pumps, made from wrecked station trailers and general repurposed steel.

But consider that at this stage the station water infrastructure would be limited to 10 portable solar panel trailer setups, 3-4 trailer mounted 2” pipelines of 3km length, two portable water tanks, two portable troughs, and admittedly, a drill rig. There would be only be one bore run at any one time, and only one bore to check on that run. Perhaps two if it was just after a move. There would be more mustering to be done, but the cattle would be much easier to handle, and looking forward to the next move. Once they got used to it they would largely move themselves. Joining and weaning would be much easier, and productivity would increase per animal, allowing the property to run less cattle for a sustainable financial return.

No doubt I’m getting ahead of myself, but I’m a big believer in first deciding where I want to be in the future, and then taking actions with that goal in mind. I like the idea of this system because I can use all of my existing infrastructure, and transition to the new system in small steps. The cost of those steps is pretty minimal, and commensurate with the rate at which I think the country will continue to recover. The exception may be buying a drill rig to drill all of the bores I will eventually need. But that’s a way off yet. I like that the infrastructure that I must make and buy will be constantly moving with the herd, always getting maximum return on investment. Because their wont be much of it, I can afford for it to be standardized and of good quality and therefor cost me less in maintenance and breakdowns. I like the positive feedback loop that will result from less cost, less time and more productivity leading to less stress for the animals and the pasture that they graze on. And ultimately, the better the condition of the pasture the more reliable the financial return, especially in dry times.

Now I just have to make the portable pipelines. I have an idea for a trailer that includes a hydraulically assisted pipe retrieval system, but we’ll just have to wait and see exactly how it pans out!

Cable reels we were given after a high voltage power line was installed on a nearby project. These are the starting point for the portable pipeline.

Cable reels we were given after a high voltage power line was installed on a nearby project. These are the starting point for the portable pipeline.