Wherever I lay my hat

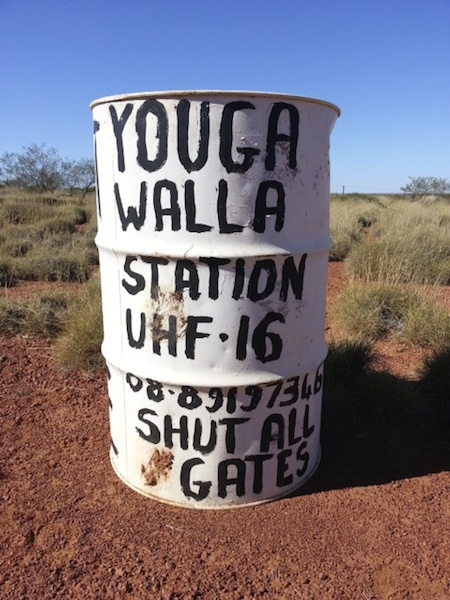

Host: Yougawalla Station

Written by Jane Sale – Manager, Yougawalla Station.

How do you know when to take the right risk? In some cases you don’t have a choice. Others, you have to ask what the worst that can happen is. When the risk pays off you feel amazing, and when it doesn’t, well we all know what those feelings are like. Sometimes we take a big risk with a large payoff. Other times it’s just a matter of trying something for the first time to realise that we like or dislike it. This is my story about how a small risk turned in to the best opportunity of my life.

I had been travelling and working in Australia for just over a year. At the time I was living and working in Melbourne. Being the typical backpacker in Australia you tend to get a bit shaky when you stay in one place too long. Don’t get me wrong I love Melbourne, but I was tired of the old struggle of trying to save money, staying out late, and waking up early, hustle bustle of the big city. I was looking for something a bit more. Something out of the city, something that felt a bit more authentic. I never dreamed that I would land on Yougawalla station. 850,000 acres in the Kimberleys.

When I first got the phone call from Haydn I didn’t even know what or where the Kimberley was. I was all caught up trying to understand him and I wasn’t sure if I heard “the Kimberley” or a persons name “Kimberley”. After hashing out some of the details with Haydn, and talking to his wife Jane I decided that moving up to the station was a good opportunity. Somewhere to save money, work hard, and probably learn a bit while I was at it. I left Melbourne pretty much on a whim in hopes that Aussies are as their stereotype suggests, friendly and honest. I hardly knew where I was going, what I was getting my self in to, and the love that I would find when I moved up to this place. And no, it wasn’t a girl. It was the work, the lifestyle, the people . . . the adventure of it all.

I flew in to Broome and landed at 6pm. By 6am Haydn was at the hostel to pick me up and take me to a place where town is a four hour drive away. Most of you would think I was mad. I just figured worst the worst case is that I work for a few weeks, hope they pay me, and my flights were covered in and out. No loss of time and a few weeks of something different. You never know unless you try right? As I said, I hoped the stereotypes were true. When we left Broome I couldn’t believe how red the dirt and sand was. It felt like a true Australian experience going out into the desert to work. I had been familiar with a few farms before but nothing like an Australian station.

It’s a bit of an odd place at a quick glance. You live in the middle of nowhere and your mail and food gets delivered by plane once a week. Not only do you work with the people you live with, but live with the people you work with. They send you out in to the middle, of the middle of nowhere and tell you to fix a bore, fence, gate etc.

They give you directions based on a few trees, a road, a gate, maybe a sign if you’re lucky. You float between asking yourself what ever got you out to a place so vast. At the same time you thank yourself for whatever decision you made that got you to a place that really shows you it’s not all about people and cities. It instills within you a sense of awe to know that the closest person to where you are is a two hour drive back at the homestead. Sometimes you don’t even see a cow or bird for the day. While fixing things like bores and fences is a big part of the job it is the cattle work itself that absolutely captured me the most.

Most people think cows are dumb. Sometimes I’m still not sure whether they are smarter than they are stupid, or if it’s that blind stupidity that leads them into looking smart. Either way there is something about seeing cows look up at you as you drive by them with their big floppy ears sticking out; senses at the ready to take off into the bush. They take off running at the sound of a car, motorbike, person, or helicopter approaching. Yet at the same time a person on a horse can practically walk up and scratch a cow on the back.

Seeing a calf or cow panic at the site of the truck is pretty funny, but there is something quite majestic and powerful about watching a full-grown bull lumber around without a care in the world. It’s the patience in which they walk off in to the bush, or up the race. They seem to know that no matter how much force other cows want to use, or we might be able to put on them, they’re still bigger than everyone else and will get there when they are ready. It’s great too, coming home at the end of a hard day and sharing the stories of everything that happened in the day. The cattle you saw freaking out, the way the old girls at the back didn’t want to walk anymore and would just keep eating grass, when the tough cleanskins finally made it in to the yards, when you thought everything was going to go to S*!% and than for some odd reason the cattle just stopped, looked in the other direction and decided, yes, they should walk calmly to the yards.

The yards are where a lot of the best action happens. Imagine taking a wild animal that sees people once a year. This animal lives in an area where it is not contained, not told where to go, not told what to eat. It just roams and does what it wants. Now take away all that land and contain it to an area smaller than the size of a soccer field. Multiply that animal by anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand and imagine the chaos.

Generally most cows will move with the herd smoothly just trying to get out of dodge of the person working near them. But not all are so easily moved up the pens and through the race. Sometimes they decide they don’t want to move to the next pen. They seem to think they are better than that. Sometimes they just say “No” and decide to jump right out of the pen. Other times they decide they don’t really like you and make you jump out of the pen. All in a days work really but at the end of the day you will find a way to get the work done, whatever it is. No matter how much they cooperate, turn around, move backwards, or sometimes don’t move at all.

As with any farm there is a lot of hard work to be done. The busy times are busy and the down time is needed. Often I am up before the sun and get home as the sun is setting. But it doesn’t really matter because tomorrow, I don’t have to get back on the same public transit route, to the same office, to work with same people I don’t really like, in a job that I don’t really like. I just look around at the flare of the sunset in the sky with it’s red, oranges, yellow, and the odd whips of cloud and think of how I am glad that the job is done, and wonder what we are up to tomorrow.

I don’t think there are too many places with amazing sunsets every single night like there is in the outback. They simply do light up the sky. It’s surprising how the sky transforms from a blue cloudless sky, to the reds and yellows that bounce, reflect, and enlighten the red dust and dirt. It amazes me that a place with so little really can hold so much life. There are no traffic jams, no sirens, so light up billboards, pubs, stoplights, or pedestrians. Just a few people working a large space, with great satisfaction. Every day is something different. Whether it’s working with animals, on your own, in a team, or with a machine, every day holds something different.

While only spending four months at Yougawalla last year, there are endless stories that, space permitting, I am unable to share in this short blog. It was hard enough to keep it as short as it was with the amount I have seen, learned, experienced, and come to enjoy. I think I knew I really did love the place when after being there for three months another worker asked, “At what point did you not want to get up for work in the morning?” “I’ll let you know when it happens”, I told him.